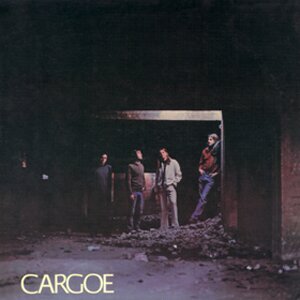

THE STORY OF CARGOE

Beautiful Sounds and Memphis Blues

CHAPTER TWO: Into the Mystic...

"When I look back, I believe that what we were really trying to do was create magic, and in magic, the closer you get to your goal, the more obstacles you will encounter. We were so close to the goal that the obstacles just became insurmountable."

"When I look back, I believe that what we were really trying to do was create magic, and in magic, the closer you get to your goal, the more obstacles you will encounter. We were so close to the goal that the obstacles just became insurmountable."

--JIM PETERS, Disc Jockey, KAKC, 1964-1970

"After the three or four days at Beautiful," Peters said, "the album was recorded, but the mix took quite some time. Bill stayed in Memphis with Rob to mix the songs, etc."

"We towed all of our equipment down there and recorded basically the same album that we were to record at Ardent," according to Phillips. "And I said, I like it here. I'm going to stay. The other guys said, well, we have to go back to Tulsa to pull our stuff together, so we can come back. So I moved in with Walker and kind of parked it there. The other guys came back a few months later."

"When we went back to Tulsa," Peters remembers, "I was still on the radio and they thought it was cool hanging out with a disc jockey. They were coming over to my house in the middle of the night, tripping and wondering what I was doing."

In Memphis, Walker was working overtime to complete the mixdown. "I was still working full-time at WHBQ, being the music director and doing afternoon drive," he said. "After I got off the air at six or seven p.m., I would walk next door to Beautiful and mix until four or five a.m. This was my first time in a real recording studio, so I was getting quite the education from some bona fide engineering geniuses, though I did not realize it at the time.

"Dan Penn and his partner at Beautiful, Eddie Braddock, had significant connections in the record business, so when the album neared completion, they went looking for bidders. Atlantic Records sent a producer named Brad Shapiro to Memphis for a listen. He offered us a deal to release the single with an option to pick up the album later. Dan wanted a deal for the whole album, so he passed on the offer."

In the meantime, the band had moved to Memphis and decided to set up on their own, as living off of Walker's salary and the meager bookings wore thin.

"When everybody moved to Memphis," Phillips said, "we just thought, well, we're a hippie band, so let's do a hippie thing and all of us move in together. We found a place that was kind of a converted duplex, upstairs being one apartment and downstairs being the other. There was a kitchen on both floors and there were enough bedrooms and living rooms that everyone could have a room. Everybody had their girlfriends and stuff. Basically, four couples moved in, then Peters came to stay for awhile."

Actually, one room was handed to a friend from Tulsa, one Bill McMichael, and there was no girl with Wisley for the first few weeks. "I went to Memphis partially because Pam, my girl, met another guy in 1968 and married him in 1969. She broke my heart. I wasn't going to get into that again."

Peters came out later. "The band wanted me to move out to Memphis," he said, "and that meant me quitting my radio show. But conveniently, I got fired because of a rumor of dope. They fired the entire staff of a number one radio station! Except for the program director, who was conveniently on vacation at the time. So I ended up taking my wife and two kids and took over one of the rooms at 1972 Cowden, the house the guys had rented. And I took a break from radio, which I sporadically did over the course of my radio career.

"By the time I got there, though, something had changed in the relationship between Bill and myself. There were words being said that probably shouldn't have been said and it affected Bill because his pride was in that band. He thought I was on a head trip or he thought I was negative about the band or something. It looked to me like the band had begun eating itself from the inside out."

A lot of the tensions came from the sessions.

"It eventually turned out," from Phillips' standpoint, "that we liked the material we as musicians wrote together rather than what we did when we collaborated with Jim. We recorded two of his songs at Beautiful Sounds, but didn't consider putting them on the album. We just had too much that the four of us had written to worry about other people's stuff. We kind of moved away from Jim at that point, I guess."

"Jim was way into theater," Wisley suggested." He was a theater major at Tulsa University, a graduate. He had this whole other world going on. He wrote some songs and we tried to put music to them. He wrote one called Carny Joe which I think made it to the Beautiful tapes, but was ultimately sidestepped. Mainly because we kept the tunes we had put together as a band.

"I don't know if you could say that we missed the boat or what, but there were some things that Jim was trying to get us to think about and do that we may have been too young to appreciate."

From Peters' perspective, it had to do with respect.

"I played a little bit with Cargoe, yes, but it came to a kind of strange end at Beautiful. Emotions were running high and I had a song that I was playing on with them, but they wanted to put my part on later. As an overdub. And I just didn't do it. I decided then that the four of them were the band. Period.

"We worked hand-in-hand, so if they needed a line or a stanza, I'd provide it. Horses -- I wrote the third verse. The middle verse of Time, I wrote.

"And they didn't give me credit for what I had done. It wasn't a conscious thing; it was a mistake. But it was a mistake I couldn't get anybody to correct. I couldn't get anybody to listen, to say when somebody contributes, you have to give him credit for being a co-writer of a song."

In spite of the tensions, everyone plugged along. Walker and Peters shopped the album and the members of the band kept playing.

Penn grabbed the guys now and again to work with him while they waited for something to happen.

"Dan would come up and say, hey, man, you want to take a hit of speed and stay up all night and write a song?" Phillips laughed. "I've got this idea. That's how loose it was. And it was fun.

"Once he came in with this line that went, 'If love was money, I could afford you honey' and I thought, well, that's about hokey enough to work, Dan. That was at night and by three o'clock the next day, we called the musicians and laid down a demo track for that song."

"That was a great tune," agreed Wisley. "It was something that Dwight Yoakam could do today and make a major hit. It was one of those boot-scootin' kind of things. And there was one Penn and Tommy wrote with the lines, 'This ain't no beer joint, it's a tear joint.'"

Penn had signed a deal for an album with Happy Tiger Records and the single If Love Was Money was released, but the album remained unreleased until 1973 when tracks from those days were uncovered and placed on Penn's 1973 Bell LP, Nobody's Fool. Members of Cargoe did receive credit on the album, but they did not play as a group on any of the tracks.

"With Penn," Phillips explained, "the work was more individual than the whole group playing behind him."

"It was," agreed Wisley. "Bill would be there just hanging out, and he and Penn would hook up or Penn would hang out with Tommy. I didn't hang around there. I don't know why."

There were drugs, mainly speed and pot.

"From my perspective," Wisley said, "there may have been a little speed or something, but there wasn't anything hard going on at the time."

While the band played, Walker and Peters worked.

"The anticipated flood of offers from major record companies did not materialize," Walker remembers. "Atlantic, for reasons we could guess at forever, still would not meet the Penn/Braddock demand for $50,000 upfront against royalties. They seemed quite sure that someone else would. They were wrong.

"Meanwhile, the band, Peters and I being the addled youth that we were, thought we were going to be the next Beatles. Dan thought so, too, and decided to put the record out himself. We'd show them! Thus was born Beautiful Records, and we pressed up a couple of thousand copies of Feel Alright as a single. After all, they were killer players. So I got them on the air."

"My station, WHBQ, was programmed by Drake-Chenault, 'inventors' of the Boss Radio format that swept Los Angeles and then the nation in 1965. Each week, the music directors at each station across the country did the 'music call' with Betty Brenneman, who was Drake's National Music Director. The lists were tightly controlled and monitored by Betty. She loved the record, but had reservations about putting it on the air -- part of the Drake formula was (does this sound familiar?) a tight playlist of proven hits with very little chance-taking.

"My station, WHBQ, was programmed by Drake-Chenault, 'inventors' of the Boss Radio format that swept Los Angeles and then the nation in 1965. Each week, the music directors at each station across the country did the 'music call' with Betty Brenneman, who was Drake's National Music Director. The lists were tightly controlled and monitored by Betty. She loved the record, but had reservations about putting it on the air -- part of the Drake formula was (does this sound familiar?) a tight playlist of proven hits with very little chance-taking.

"Somehow, I talked her into letting us try Feel Alright on WHBQ. It hit. The phones lit up. The record sold. Of course, Cargoe, Peters and I were so deep into Beautiful financially that we were light-years away from seeing royalties. And all six of us were living on my radio salary, although once the single was all over the Memphis airwaves, the band got some pretty good bookings and were able to contribute to the communal welfare."

The story was not so simple, however. Peters remembers a phone call with Brenneman during which she argued for the inclusion of the single on Drake's playlists.

"Brenneman had picked it up to go on two or three stations," he said, "but the record came back from the pressing plant with a little bit of the first chord clipped off. Rob said, I'm not putting a record under my name out that isn't right. And Betty said, but Rob, I didn't even notice it. Nobody even knows, and he said I know. He absolutely put his foot down. I wanted to say, Rob, I think you'd better reconsider, but he was in the middle of this phone call with Betty."

An agreement must have been reached because it was added to the playlists of KAKC and WHBQ. It reached #4 and #6 in each of those markets.

Things did appear to be looking up, even to Peters, who was once again feeling the tensions within the group.

"God, man," he said, "these guys were so influential at that time. It was unbelievable. Every band and music person in Memphis gathered around them. Including (what became) Big Star. Including this band called The Knowbody Else that later became Black Oak Arkansas. Including John Fry (Ardent's head man)."

Then the records ran out. With no money to repress, the single was dead.

"Weeks turned into months," said Walker. "Feel Alright had run its course, still no record deal and we're beginning to starve. Girlfriends entered the picture (and the house), nerves got frayed, cynicism set in, blah, blah, blah. We were young and impatient."

But not all of the cards had yet been played. In a last ditch effort, Walker and Peters headed to Los Angeles.

Peters remembers it only too well. "We made a trip out and knocked on doors and got an offer from Epic Records. We went to see Walter, the attorney. We had to walk over there and it started to rain, which put us in a pretty bad frame of mind. When we get there, Walter said, you know, you have a standing offer of $25,000 on the table right now from Epic. The thing was, Penn had told us, don't come back with an offer less than $50,000. We didn't know what to do. That was the top offer we got. We were only out there for two weeks. My feeling was that had we been there for four weeks, we would have gotten the 50 grand because once the doors are open, L.A.'s a great city. That's why great movements start there.

"What I found out later was that Penn and his partner were trying to hold on to that studio, but they didn't have any hits coming out. They therefore didn't have any money coming in and payments were due."

Penn had received a loan from Union Planters Bank and was being pressured to pay. This same bank would play a major role in the dissolution of Stax Records.

CHAPTER ONE: Living On Tulsa Time...

CHAPTER THREE: The Things We Dream Today...

CHAPTER FOUR: Delusion and Dissolution...

CHAPTER FIVE: The Painful Look Back and...

CHAPTER SIX: Such Is the Power of Music...

Supporting the Indies Since 1969