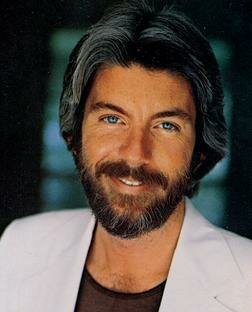

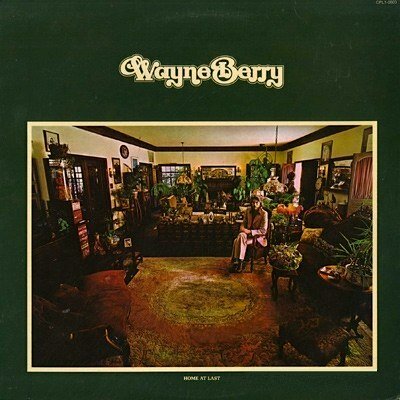

WAYNE BERRY

Home At Last

“There's an old Webb Pierce tune called I Ain't Never,” Wayne Berry said in the course of an interview not long ago. “It was one of the definitive pre-Rock & Roll songs in terms of not only the structure of the tune, but the musicianship and whole vibe of how the session came off. It is a phenomenal prototype for a two minute Rock & Roll preamble. It worked itself into the DNA, I guess, of a lot of musicians--- especially Southern musicians.”

Huh. Webb Pierce. I know a little of Webb Pierce. There wasn't a tavern jukebox in the 1950s logging town of Sweet Home, Oregon where I grew up that didn't have at least one Webb Pierce record on it--- some of them, more. But Rock & Roll? Now that I think about it, a lot of the old Country & Western musicians were playing Rock & Roll (and it was Country & Western back then, though Nashville would soon drop the & Western in an attempt to appeal to a wider audience). Admittedly, they didn't say they were playing Rock & Roll at the time, but you dig through the discographies of Pierce, Hank Williams, Pee Wee King, and young turks like Ferlin Husky, Faron Young and Marty Robbins and you will find plenty.

This is why we need to talk with the Wayne Berry's of the world. To understand that Rock & Roll did not start and end with Elvis and was around long before the term was even coined. That music, as important as it was and is, is but one segment of this existence we call life. That the story of music is neither one Hollywood success story after another nor a string of tragedies at the business end of a needle. That while music can be and is a business, it is so much more.

Wayne Berry knows. He grew up in 1950s Nashville, the epicenter, even then, of Country & Western. He grew up in the South, where religious and gospel music were a thread in the fabric of everyday life. While he didn't start out to be a serious musician, he became one, crossing paths with people whose names are now legend: Felice & Boudleaux Bryant, John Loudermilk, Noel Paul Stookey (of Peter, Paul and Mary) and later Bob Dylan, Kris Kristofferson, Jackson Browne, Clive Davis and a hosts of others in Nashville, New York, and L.A.. He remembers them (how could he forget), but as he knew them and not as what they became. They were people, some of them good friends, but just people, doing what they wanted or what they had to do do make a living.

Wayne Berry knows. He grew up in 1950s Nashville, the epicenter, even then, of Country & Western. He grew up in the South, where religious and gospel music were a thread in the fabric of everyday life. While he didn't start out to be a serious musician, he became one, crossing paths with people whose names are now legend: Felice & Boudleaux Bryant, John Loudermilk, Noel Paul Stookey (of Peter, Paul and Mary) and later Bob Dylan, Kris Kristofferson, Jackson Browne, Clive Davis and a hosts of others in Nashville, New York, and L.A.. He remembers them (how could he forget), but as he knew them and not as what they became. They were people, some of them good friends, but just people, doing what they wanted or what they had to do do make a living.

GROWING UP SOUTHERN...

The South of the 50s was hardly the South as we know it today. Media was mostly regional, if not local, television sets a luxury and national broadcasts just beginning to make an impact. The first coast-to-coast broadcast took place on November 18, 1951, Edward R. Murrow's See It Now opening with shots of the east and west coasts on a split screen, the first time it had been done. Radio, established as the dominant medium alongside the newspaper, had already begun to change, many smaller local stations eschewing networks and “variety” programming for music in record form. Those stations soon would be known more by the music they played than anything else.

Music at the time was way more than radio, but radio was the catalyst for the young.

“I grew up with a mix of church music and what was happening in the mid-50s,” Berry said. “Age-wise, had I been three or four years older, I would have probably gotten much more involved in music as a profession, I think, because I was about three or four years behind the Rockabilly days at its inception.” Of course, it wasn't called Rockabilly at the beginning. “I was growing up before they labeled the music,” Berry continued, “before there was any real definition of musical genres. It was organic. It was everywhere. The Everlys and The Louvin Brothers and other early country artists were playing rockabilly but didn't know they were because there was no such designation then. That’s just not how that evolution happened.”

It took a whole lot of media involvement--- radio, newspapers and television with the help of the record labels for it to get to that point. The kids didn't care. While it evolved and what it evolved into was not a consideration. The only thing that mattered was the music.

“My cousin and I grew up in the Church,” remembered Berry, “and both learned to play guitar through his dad, who played guitar. We had aunts and uncles who were musicians, so it was natural. So at a very young age, we were the local Everlys. We sang all the time. We sang at church and at parties. We were too young to play gigs, being only thirteen or fourteen, but that was how we started.”

The Everlys phase worked for a time, but high school presented new opportunities and there was growth. Berry spent time honing his skills, passing through a handful of rock and folk groups and, through a series of events or contacts he cannot remember, ended up hanging out with Felice and Boudleaux Bryant.

“I was in early high school,” he said, “and had a license and a car. My dad was in the car business so I had a car from the time I was fifteen. That changed my whole childhood because I was mobile.

“The Bryants lived about 25 miles on the other side of Nashville up on Old Hickory Lake. In those days, it was like going out in the country. It was a long haul. How the linkage took place, I have no clue. The Bryants were pretty much in their heyday then, when the Everlys things were huge hits. I was an acquaintance and it certainly was not a mentoring relationship at all, but I had maybe a year and a half interaction with them. I was at their house when they were writing. They were adults, maybe 18 or 20 years my senior.

“The Bryants lived about 25 miles on the other side of Nashville up on Old Hickory Lake. In those days, it was like going out in the country. It was a long haul. How the linkage took place, I have no clue. The Bryants were pretty much in their heyday then, when the Everlys things were huge hits. I was an acquaintance and it certainly was not a mentoring relationship at all, but I had maybe a year and a half interaction with them. I was at their house when they were writing. They were adults, maybe 18 or 20 years my senior.

“I knew they were writing hits, but did I know history was in the making? No. Not at all. I wasn't cognizant enough to think, do they know what they're doing. The other side of the coin is that I wasn't starstruck, either. I wasn't going, gee, they're writing hits for people and wouldn't it be great if I could do that. I mean, there was a mentoring spirit about the whole thing, but it wasn't a mentoring relationship as such because it never got to there. In retrospect, it's almost surreal. I really don't know how that happened at all.

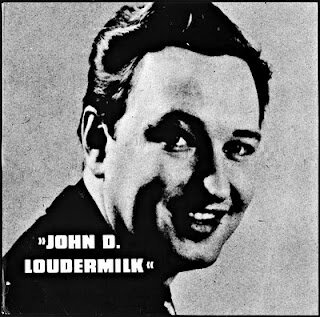

“The same thing happened with John D. Loudermilk and I don't know how that happened, either. Somehow I fell into about a year's hang time with him. He had a little office in a really small studio--- a writing office in what was basically a demo studio. It was in an obscure building in an obscure part of the city. Again, I was younger and would sit to one side while he sat with artists and agents pitching tunes. That really affected me in a “Tin Pan Alley” sort of way.

“The same thing happened with John D. Loudermilk and I don't know how that happened, either. Somehow I fell into about a year's hang time with him. He had a little office in a really small studio--- a writing office in what was basically a demo studio. It was in an obscure building in an obscure part of the city. Again, I was younger and would sit to one side while he sat with artists and agents pitching tunes. That really affected me in a “Tin Pan Alley” sort of way.

“This all happened when I was in high school and playing in bands, but it was another couple of years, late high school, before I was doing anything that could be considered professional. The transition from playing the Legion Hall to actually pitching tunes came a couple of years after that. I mean, I didn't parley my encounters with the Bryants or Loudermilk in terms of them being successful songwriters. It wasn't a networking thing at all. It wasn't like I met people because I had hang time with them. There was a progression there, but my involvement with them didn't open doors for meeting other people. On the backside, though, I did get more involved with “The Row” (Music Row in Nashville) and started pitching tunes before I even knew I was pitching tunes.”

Of course, pitching tunes presumes tunes to be pitched. The process of songwriting was subliminal for Berry.

“(Nashville) was an awful, awful environment. I hated it. I wasn't pursuing fame and fortune as such. It was more art for art's sake, if I can put it that way. But the social dynamics in terms of how I looked at society and the culture in and out of the music business was just awful. The only reason I wasn't a dyed-in-the-wool hippie was that I had a gig--- I had income--- and I had some aspiration toward something that resembled a career on some level, as opposed to just the turn on, tune in, and drop out mantra.

“(Nashville) was an awful, awful environment. I hated it. I wasn't pursuing fame and fortune as such. It was more art for art's sake, if I can put it that way. But the social dynamics in terms of how I looked at society and the culture in and out of the music business was just awful. The only reason I wasn't a dyed-in-the-wool hippie was that I had a gig--- I had income--- and I had some aspiration toward something that resembled a career on some level, as opposed to just the turn on, tune in, and drop out mantra.

“I was seeing a contradiction, for instance, in terms between what was happening in the church at large and what I was finding in Scripture. At the time I was growing as a young Christian, my understanding in Scripture was that races should be reconciled. Now, I am not talking about all Southerners but about my family and my church family. And I am not talking about racism nor am I talking about bigotry.

“I became aware of a certain aspect of--- I am hesitant to call it hypocrisy because the people I grew up with were not really hypocrites. I wasn't imprinted with race bias. My problem was in dealing with pre-Civil Rights laws up through the passing of the Civil Rights laws.

“All of the churches were segregated because the culture was segregated. I wasn't in a church which wouldn't let African Americans in. African Americans and Anglos just did not associate with each other except in certain work situations. It just wasn't part of the culture. So a church which wanted to breach that subject would have been really bold and cutting edge to take that stand based on Scripture. It just didn't happen.

“I got very involved in left-wing politics as a teenager because left-wing politics was so foundational to the folk movement. So many people who were voices in folk music were standing on platforms which were basically leaning to the left politically.

“I wasn't politically active regarding the politics. I wasn't even old enough to vote. I wasn't as concerned about the Senate and Congress and the White House as much as the liberal dynamic which should have been happening on the cultural and relational level. Civil Rights was a big deal for me.

“Those two sensibilities were active within me and the way that translated was that I became very uncomfortable living in the South. The political dynamic needed to change and wasn't, and the biblical dynamic needed to change and wasn't. I was very frustrated by that. Those two things took root in me and I carried it with me in my lifestyle and my perception of writing.

“For me in those days--- and I'm talking about the late fifties, I didn't hear much music from the West Coast and the Midwest music I heard was more Country & Western and Country Swing than it was country rock. So, to me, the genesis of the whole Rock & Roll vernacular was either citified--- Chicago, St. Louis, etc.--- or within that whole grouping of the Southern states.

“I think if I'd grown up outside the South, my music would have been a lot different. A lot different. Fundamentally, in terms of formative Rock & Roll, there were two streams for me. There was the Southern, and by Southern I mean everything below Kentucky to the Gulf, I guess, including Lee Dorsey, Fats Domino, Little Richard and James Brown--- all the way over into the Carolinas. That, to me, was The South. The other stream would have been St. Louis, Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit. I'm thinking of the Chuck Berry stream--- an urban stream of people who clearly had some sensibility which connected them to the South but who weren't Southern.

“I think if I'd grown up outside the South, my music would have been a lot different. A lot different. Fundamentally, in terms of formative Rock & Roll, there were two streams for me. There was the Southern, and by Southern I mean everything below Kentucky to the Gulf, I guess, including Lee Dorsey, Fats Domino, Little Richard and James Brown--- all the way over into the Carolinas. That, to me, was The South. The other stream would have been St. Louis, Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit. I'm thinking of the Chuck Berry stream--- an urban stream of people who clearly had some sensibility which connected them to the South but who weren't Southern.

“Chuck Berry wanted to be or aspired to be the next Nat King Cole. Of course, it certainly didn't come out that way when he plugged in his guitar. Look at Memphis. He certainly didn't write that because he grew up near Tupelo. What I guess I'm trying to say is that there was something in the air that was connecting him to what was happening in the South, musically.

“And look at Buddy Holly's influences--- how he ended up multi-tracking and doing orchestration on what otherwise would have been country ballads. Somehow, he made the connection which turned that into an urbanization of what he was playing when, in fact, he was just part of a garage band.

“That whole process was very organic. The first two professional encounters I had, I somehow got involved or got an introduction or got my foot in the door at Acuff-Rose and that somehow parlayed into meeting George Hamilton IV. The first song I wrote that was recorded was for a George Hamilton IV album. How it happened, again, I have no clue. I think I was still in high school, but I don't even remember that. I can't even cite the album or anything and I played on the session. It's crazy because I was in no way involved in anything that resembled an inner circle. I played on the session because I was in bands, I guess, and had started playing out locally. Folks started knowing who I was from that.

“That whole process was very organic. The first two professional encounters I had, I somehow got involved or got an introduction or got my foot in the door at Acuff-Rose and that somehow parlayed into meeting George Hamilton IV. The first song I wrote that was recorded was for a George Hamilton IV album. How it happened, again, I have no clue. I think I was still in high school, but I don't even remember that. I can't even cite the album or anything and I played on the session. It's crazy because I was in no way involved in anything that resembled an inner circle. I played on the session because I was in bands, I guess, and had started playing out locally. Folks started knowing who I was from that.

“The folk era had come and was going. There were folk clubs around and there were maybe half a dozen of us who were writing outside the box. We clearly were not pursuing being country writers an there was clearly no home for us in Nashville. Lee Clayton and Chris Gantry. Those names sound familiar? Gantry's big break would have been Dreams of the Everyday Housewife. I remember when Glen Campbell picked it out, but I don't remember how the process worked. I do remember when Chris got the word that Campbell was going to cut the tune. We were all in that loop and doors started opening to us and people began approaching us about tunes. I am not trying to equate my level of talent with theirs, but one of the reasons I think their level of prominence was different from mine was that they stayed planted. They didn't want to become Music Row celebs, but they did want to write from Nashville and build a career from here. I didn't. I was looking for some way out. I finally moved to New York and then to California.”

Of course, music came at a price. Berry's parents, as supportive as they were, were leery of such a career move.

“(My parents) were supportive of me because they loved me,” Berry explained, “but they were real unhappy that I was going down that road. I grew up with beautiful parents. They were supportive in that they would say that this wasn't a good decision, but they also said if I was going to keep monkeying around with this, they hoped I was successful at it. I remember them on more than one occasion saying, 'We just never saw this coming. Why are you involved in all of this?' And my response was, 'Have you not been paying attention to my life?' I'd had music around me my whole life. At that point, it seemed to me that somehow they were missing the obvious.

“Those were days when so many things were happening culturally, too. Pot was becoming big-time big-time illegal. The environment we were living in here--- the whole concept of a counterculture or hippie lifestyle--- we stood out like sore thumbs. The counterculture in Nashville in the mid-60s was a joke.”

The Call of the Big Apple.....

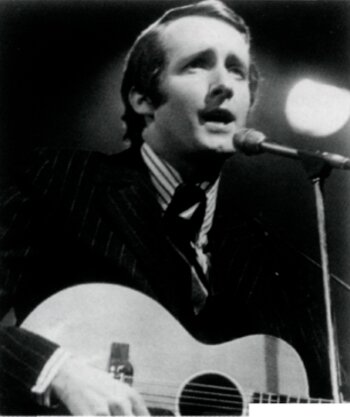

The move to New York was precipitated by a friendship developed earlier with Noel Paul Stookey of Peter, Paul & Mary.

“I met Peter, Paul & Mary on their first tour of the South when I was fourteen or fifteen,” Berry recalled. “I met them at a concert and on the front end became kind of a groupie for the first eighteen months or so of our friendship. I managed to go to a couple of concerts which were within a reasonable driving distance and the next time they came South, I had a car and was more mobile. As my circle began stretching out, any time they played within a driving distance that a teenager thinks is reasonable, which could be several hundred miles, I showed up and eventually got connected to them. That was during the Hootenanny era, when folk really came on. At that point, I became friends with them and they had friends who were starting to become friends of mine.

“I met Peter, Paul & Mary on their first tour of the South when I was fourteen or fifteen,” Berry recalled. “I met them at a concert and on the front end became kind of a groupie for the first eighteen months or so of our friendship. I managed to go to a couple of concerts which were within a reasonable driving distance and the next time they came South, I had a car and was more mobile. As my circle began stretching out, any time they played within a driving distance that a teenager thinks is reasonable, which could be several hundred miles, I showed up and eventually got connected to them. That was during the Hootenanny era, when folk really came on. At that point, I became friends with them and they had friends who were starting to become friends of mine.

“The first publishing business I had was with Paul Stookey. He funded my original publishing company, so I guess he was more of a mentor in a business sense more than anything at that time. (I played) my first real sessions (with Paul)--- real sessions rather than demo sessions. They weren't artist-driven. They were just like demos, but something more than songwriter demos. They were done in New York, Stookey producing, with a bunch of New York players. We did them at the Columbia Studio in NYC where Big Pink was recorded, and Moondance. The first, quote, big-time session work I did was in the City with Noel.

“I was playing anywhere I could, but that was the genesis of how I became an artist, in terms of recording. I didn't cut a deal out of that, but that was where the 'go' button got pushed. That was what really drew me to New York. At that point, everything had kicked in, what was happening in terms of the counterculture and my future in music, and what was happening was the West Coast.

“The level of communication among musicians was small (back then), but I didn't realize that there was a Berlin Wall built around the South. It turned out to be a huge advantage because roots music and groove music and music that was more spontaneously birthed and recorded--- or captured, if you will--- was much more the way the music in the South was handled. The recordings on the West Coast and in urban environments were much more professional in their approach. It doesn't mean they weren't good, rather that they didn't have as many elbows in them as Southern music did. The playing and the grooves were just a little too tight for a Southern boy. I think 'feel' music and 'attitude' music and the more organic development of rock music is truer in a sense, if you stay closer to the roots.

“Radio played a huge part in songwriting, but I think it was also industry-driven. There were so many people involved in promotion and management who were active in the business who were either based in urban environments or who were dealing out of the trunks of their cars down South.

“When I finally got to the West Coast (I was probably nineteen or twenty) and started interacting with other musicians, I found out there were national hits by famous artists which were covers of songs I had originally learned in the South. I had never heard the national hit because they didn't get airplay in the South. The South promoted the local original artists. I had no idea lots of tunes I grew up hearing were cover hits by other artists until I went to the West Coast.”

Los Angeles, Record Mecca.....

“(My move there) was like Creeque Alley--- the John Phillips narrative of where the Mamas and the Papas came from. I was just a couple of years behind them and, fundamentally, what they did was what I did. When they went, this is crazy living here, we're going to freeze our tails off and we have no money anyway, so let's head to California. I did the same thing, the only difference being that I had come up out of the South instead of New York City.”

When Berry got to Los Angeles, he found himself surrounded by numerous musicians, most from out of state, but music wasn't everything at that point.

“I got involved with The Underground and The Resistance,” he said, “helping people to evade the draft. That was a direct result of everything that had been keyed in during my mid-teen years because of the Civil Rights Movement. In those days, if it had to do with Republicans or conservatism, my path was in the extreme other direction. In a sense, you can trace a lot of the hippie culture and movement to that. Whether the hippies were going to vote Democrat or not was not the point. The point was that culture needed to change and it needed to change in a liberal context.”

Still, music was Berry's main focus.

“The whole process was very unstructured ---- it was the 60’s, you know. At that point, anybody who didn't have roots in California, which would have been pretty much everybody except Jackson (Browne)...” A pause for laughter. “... was doing exactly what I was doing. And the only difference between Jackson and the rest of us was that he had grown up just right down the road from Hollywood. Everyone else was a transplant. It was like Close Encounters of the Third Kind--- being drawn to a mountain and not knowing why. Everybody was drawn to L.A. and no one knew why.

“(Of course), nobody cared. We were all too loaded to care. Nobody was looking at what we were doing from a sociological standpoint. It was all musically and culturally driven. Now, this was before the Southern California Sound. There were already huge artists there. And I'm not saying there wasn't already a music business.

“Jackson and Longbranch & Pennywhistle (J.D. Souther & Glenn Frey)--- there were dozens, and a lot of these people who were successful were never really successful on the national level. If you want to date it, this was just on the backside of the Buffalo Springfield breaking up and Poco forming. All of us were going, what do we do with all of this unction that's inside us. And no one at that point was saying I want to be a Rock & Roll star and make a lot of money. Nobody.

“It was all about the music. Well, it wasn't all music-driven, but that was the catalyst. I mean, I didn't go out there to get signed as such. I certainly wanted to be out of the South, but all of that was connected to my music. I just did not want to live in the South.

Signing With Capitol.....

“What I ended up doing when I got to California was getting signed to Capitol Records as a solo artist. Then I turned right around and came back to Nashville to put together my first project, which you may know nothing about. It was recorded in Nashville but never released. That project, back then, would have been considered progressive and out-of-the-box. We used all the players who were up-and-coming players and not part of the country music establishment. They were more hip and trying to break into the business but couldn't get first-string sessions, even though they were hot players.

“What basically happened was I got teamed up with Larry Butler, who produced records out of Nashville. He later produced five or six of Kenny Rogers' albums, but then he was basically just a Capitol Records in-house producer based in Nashville.

“Capitol on the West Coast was very high on Butler. They flew him out to the West Coast and he and I sat down and found out that we had basically the same kind of roots in terms of what we liked and disliked. He was disinterested in the A-Team players in Nashville because they were so ensconced in country music. At the time, Nashville was very exclusive and there was little pop music to speak of. Or R&B music. If R&B came out of Tennessee at all it came out of Memphis. Nashville was this kind of closed universe. But there were these young players trying to break into session work who were influenced by music other than country. They were looking for opportunities to play. Larry wanted to use all of these players and I said that sounds perfect. So he put those session players together and I came back to Nashville and we recorded the album.

“I didn't know the players from when I left because guys like Lee Clayton, Chris Gantry and I were already labeled outcasts because we were more hippie than redneck. The guys playing on all the sessions and making money in Nashville, like I said, all had redneck sensibilities. They didn't want to know about us and vice-versa. So it kind of turned out to be a transitional mix of players on the sessions.

“Do you know Fred Carter? He was part of the Nashville scene, but influenced players like Roy Buchanan and Robbie Robertson. Fred had played on Simon and Garfunkel stuff and was kind of a guru for session players. Now that I look back on it, at his age and with his experience, he was probably the contractor on all of the dates.

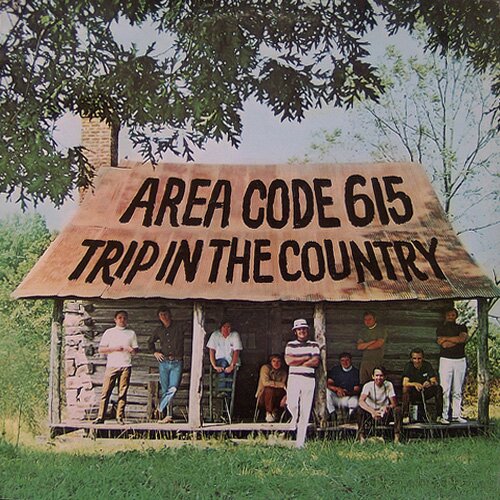

“David Briggs. There was this band called Area Code 615 which had all of those progressive players. And there was Norbert Putnam, who was from Muscle Shoals. The guys from the rhythm section, in fact, were what would have been considered second string to the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. The guys who were with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section were getting all the work and the guys who couldn't get in moved to Nashville. That's how Briggs and Putnam got up here. Norbert played bass, Fred Carter played guitar, Briggs played piano and Jerry Carrigan, who became a huge session drummer in Nashville, played drums. Those sessions were only the second or third he'd played on.

“David Briggs. There was this band called Area Code 615 which had all of those progressive players. And there was Norbert Putnam, who was from Muscle Shoals. The guys from the rhythm section, in fact, were what would have been considered second string to the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. The guys who were with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section were getting all the work and the guys who couldn't get in moved to Nashville. That's how Briggs and Putnam got up here. Norbert played bass, Fred Carter played guitar, Briggs played piano and Jerry Carrigan, who became a huge session drummer in Nashville, played drums. Those sessions were only the second or third he'd played on.

“Shortly after those sessions, all of those guys began to play more and then Area Code 615 got put together. They were not only that band but were also the tour band for Ronnie Milsap. While doing those things, they networked with a lot of people. That is how Putnam got work on Dan Fogelberg's first album, which was really Norbert's first big album that was not a Nashville project, although a lot of that album was recorded in Nashville.

“We recorded the album at a place called Woodland Sound Studios, which was a relatively new studio at the time. What happened, fundamentally, was that I shot myself in the foot by not going to California to pursue an artist's career as such. I had gone because that was where I was going to. What I really had in my gut was to put a band together. So between finishing the tracks, mixing them and getting the package ready for release, Timber happened. It wasn't called Timber, but all of the players who became part of Timber materialized over those few months.

“When I went to Capitol and started talking about the album release and the tour, I said, well, I don't want to go out as a solo artist because I am not a solo artist. I want to go out as a band. I'll front the band, but I want the band I am in now to be my band. That is how I wanted to support the project. The execs at Capitol went crazy. They said, we signed you. We don't care who you're playing with, but we didn't sign that band, and we got crossways with each other. I said, okay, but I'm, not going out as a solo artist, so we stalled. My contract lapsed and that album was never released.”

It seemed almost to set a pattern for Berry and the musicians who surrounded him.

“Such as it was,” he explained, “the labels never hung us out to dry as such. A lot of what happened was us shooting ourselves in our own feet. In the very same way that I told Capitol I was not a solo artist, which was a very stupid thing to do, in retrospect, because that was what they had signed. As a kid, that was an upstart position to take. I'm sure, career-wise, it would have been advantageous to have paid attention to the fact that they had given me a bunch of money and had supported me and believed in me, as opposed to walking in arrogantly and saying, well, I'm no longer a solo artist, what do you think of that.

“Of course, I am talking totally in retrospect. It was certainly a lousy career move because it wasn't like I didn't want this label because they didn't appreciate who I was. That would have been another story. But they were very supportive.

“Just the fact that they put me together with Larry Butler. Larry was a wonder boy at that time. Everything he was touching was taking off. At the time, I was merging into a singer/songwriter and teaming up with Larry put me in good stead.

“But it was not what I went to California to do. Bands were always what I wanted to do. I had really given no thought about what that meant to a record company which was trying to put together a stable of artists. I was dismissive of all that. That attitude carried through not only in my life, but in a lot of other artists lives as well.”

Thus Began Timber.....

Thus it was that Berry went from an artist with a label to a band with no label. From an artist with an album to a band struggling to find its legs. The seeds of that band, Timber, were planted when Berry ran across another Tennessean, George Clinton.

“George had ended up attending the college I had attended, Middle Tennessee, after I had left. I had some degree of campus notoriety due to the singer/songwriter thing so he knew about me, but I didn't know him. I was already in California and he came out there to try to beat the draft. I was involved in the Resistance and that is how we met. He had not come out to be in a band, but that in effect is what happened.”

In the midst of the Capitol debacle, the two began looking around for players. They found what they needed in Roger Johnson, Judy Elliott and Warner Davis. They seemed to mesh well and Berry was satisfied. They wrote songs and rehearsed and not long after Berry escaped the dust from the Capitol implosion, they made their move.

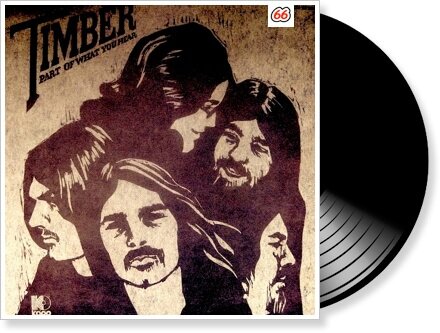

“Timber started playing out and it wasn't long before we signed with Kapp Records,” Berry said. “Kapp at one time had been a fairly big label, but when we entered the picture had almost gone dormant. At the time, they were a poor stepchild at Universal. They had just changed upper management and a new exec who had just come in had gotten wind of us through Warner Brothers, with which I had a publishing arrangement. I don't remember the literal playout, but we somehow got signed. We were going to be a startup band for them or something. And that is when we recorded the first Timber album, Part of What You Hear.

“Timber started playing out and it wasn't long before we signed with Kapp Records,” Berry said. “Kapp at one time had been a fairly big label, but when we entered the picture had almost gone dormant. At the time, they were a poor stepchild at Universal. They had just changed upper management and a new exec who had just come in had gotten wind of us through Warner Brothers, with which I had a publishing arrangement. I don't remember the literal playout, but we somehow got signed. We were going to be a startup band for them or something. And that is when we recorded the first Timber album, Part of What You Hear.

“When the album was completed, we toured the Midwest and the West Coast up into Canada. We ended up playing quite a bit in Vancouver B.C. and built a small following there as well as in Seattle. There was an area in Vancouver at that time which was being renovated and in the midst of which someone built this really nice club. We weren't the house band, but we opened the club and played there a number of times. We started building a following out of that.”

Timber, though, soon found themselves cut loose.

“It wasn't that Kapp didn't know what to do with us,” Berry explained. “It had more to do with their attempt to re-energize the label. While we were out doing what we were doing, this guy from England, this John guy (Elton), got signed. I remember coming back from a tour and meeting with some execs to work out a big promotion on our album. When we went in, they were so excited about Elton John's album that we ended up listening to it the whole time. I remember thinking that that was probably not a good sign.”

Berry laughed, but it had to be funny only in retrospect. Luckily, the band was without a label only a short time.

Enter Elektra.....

“When Timber signed to Elektra, it was basically a small studio with three offices and an exec office,” Berry remembered. “It was a really small label, but they exploded very quickly. They had artists, for sure--- The Doors, Judy Collins, etc.--- and Elektra had made a bunch of money. I'm not sure of the timeline, but I seem to think that Jac Holzman (founder and CEO of Elektra Records) pre-dated the whole Clive Davis era. Holzman had the same kind of influence in terms of his savvy. Well, more like John Hammond, I guess. Holzman, on the West Coast with Elektra, was a bit like Hammond had been with Columbia on the East Coast. He just knew how to pick artists, or it seemed like he did.

“Somehow, Holzman heard about me and the band. I don't remember how we left Kapp--- whether they dropped us or we walked away mad. Those were the hallucinogenic years. But Jac signed us. He signed us personally to the label and during that season, everything just exploded. All of the management people--- David Geffen and his whole camp--- were just starting out and had just signed the pre-Eagles, meaning the Eagles before they were the Eagles, back when those guys had just been incorporated into Linda Ronstadt's band. And there was Jackson Browne. Artists were just coming out of the woodwork. Money was flowing hand over fist. The Elektra stable started growing and we were in that mix.

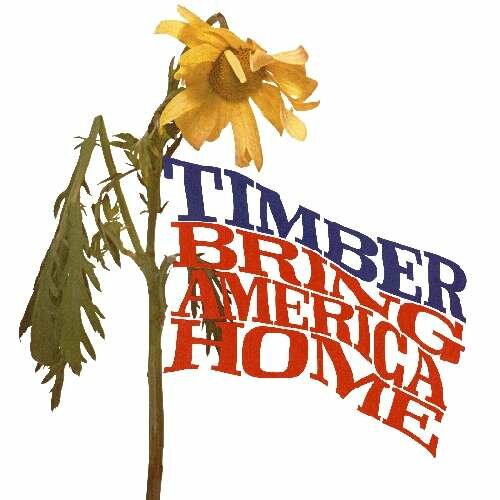

“We recorded the Bring America Home album and toured and sold some records and then the band basically imploded, which was also a part of the culture at that time. In fact, by the time we got to Elektra, the band had been beaten up enough with internal squabbles. George Clinton was feeling the need to extricate himself from that as did I, so the band just unraveled.

“We recorded the Bring America Home album and toured and sold some records and then the band basically imploded, which was also a part of the culture at that time. In fact, by the time we got to Elektra, the band had been beaten up enough with internal squabbles. George Clinton was feeling the need to extricate himself from that as did I, so the band just unraveled.

“By that time, I had made a lot of friends in the music business. Everybody back then was playing on one another's projects or helping out with demos. Some were having hits and others were losing contracts so you never knew who had money and who didn't. I ended up doing demos of some tunes I was writing. I pulled in a bunch of players for a session. I had gotten pretty close to Henry Lewy. Henry was a key engineer and was at that time working a lot with Joni Mitchell at A&M Studios, so Henry and I ended up doing some demos there.

“Not long after, a secretary at RCA called me and said, 'I hope you won't be mad at me.'. I asked what she had done and she said, 'well, I played your demos for someone here at RCA and I didn't ask your permission. They want to see you.' So I 'took a meeting' with RCA's A&R staff and that's how that whole solo thing surfaced. In a way, I walked right out of Elektra and into A&M where I was a solo artist for a short period. I think they only released the one single, though I believe we recorded three or four other sides.”

The meeting at RCA did result in a contract. The A&M deal was loose at best and Berry figured it had run its course. When the contract was signed, Berry contact old friend Norbert Putnam, with whom had worked on the Capitol project.

“Norbert and I put the sessions for Home At Last together. The players I mentioned who were swapping off on each others' projects? The guys who played on those sessions were who all those guys were.

“Norbert and I put the sessions for Home At Last together. The players I mentioned who were swapping off on each others' projects? The guys who played on those sessions were who all those guys were.

“What happened was this. I was in L.A. and the players I had a relationship with ended up being the L.A. band. In Nashville, Norbert had pulled a bunch of players together. They later basically became Area Code 615.

“Between the Capitol project and Home At Last, Norbert had risen in terms of recognition and had opened his own studio. He was producing and had players all around him who were hot shots. So Norbert and I came up with this crazy idea. Why don't we go where we want to go and use who we want to use? So he flew out to the West Coast and we recorded three or four tracks there with those guys and then we went out to Nashville and used those Nashville players and then we went down to Muscle Shoals where Norbert was from and used the Muscle Shoals rhythm section. It's an amazing album in terms of what we pulled off. Anyone who knows music history can look at the credits and see that.

“I guess out of that whole bunch, the rhythm section would have been the only musicians who had a reputation by that time. But all the other players went on to have huge careers. It was a wonderful, wonderful experience.

“Paul Simon had been at Muscle Shoals a few weeks previous to us. I'm guessing he was working on his first solo project. So the rhythm section was winding down and mixing some of those masters. I was in awe. I was in Muscle Shoals, a studio which had produced so much good music.

“Back in L.A. we probably used two or three different studios, but there were some fantastic players who worked on the album. Like Jesse Ed Davis who played on, I think, two tunes. Jesse came in cold one night. That slide solo on Black Magic Gun? He came in, sat down, put the headphones on and we said, we'll play it down for you. I turned to Norbert and said just hit record. He did. Jesse had never heard the track and did it in one take.

“The exact same thing happened in Nashville. We were recording Gene's Tune and thought we needed a fiddle, so Norbert called Johnny Gimble. When Gimble walked in, Norbert said, I'm going to run the track but I'm going to record it. And that was one take. Gimble just played against the track. If you go back and listen to Gene's Tune, in the back there is a fiddle ride at the end of the song. You can hear slight hesitation in the notes he's playing because he had no idea whether the tune was ending or not. (laughs) It was remarkable. I was moved to tears. He was such an incredible player. I was awestruck to have him playing on one of my songs.”

“The exact same thing happened in Nashville. We were recording Gene's Tune and thought we needed a fiddle, so Norbert called Johnny Gimble. When Gimble walked in, Norbert said, I'm going to run the track but I'm going to record it. And that was one take. Gimble just played against the track. If you go back and listen to Gene's Tune, in the back there is a fiddle ride at the end of the song. You can hear slight hesitation in the notes he's playing because he had no idea whether the tune was ending or not. (laughs) It was remarkable. I was moved to tears. He was such an incredible player. I was awestruck to have him playing on one of my songs.”

The album completed, Berry began organizing the followup.

“RCA was pretty high on the album and put a lot of money into the whole project. I put a road band together, sort of like what happened with Timber. RCA put together a pretty big promotion campaign and even put a big billboard on the Strip.

“It was at that point that I got involved with management out of New York--- a guy named Peter Rudge. He had been a road manager for The Who and The Rolling Stones and had come to the States to set up an American office. He knew what he was doing in England and knew what he was doing as far as The Who and The Rolling Stones were concerned. He wasn't a lacky. But he didn't know what to do with me or how to operate in America. Well, let's put it this way: It was the wrong time for me to get involved with someone who was just taking on clients.

“Rudge helped ruin that tour. It wasn't all his fault. On the one hand there was an impetus for this career to break open and on the other, there were situations.

“Case in point. You would have thought that it would have been a great fit. You would have thought that I would have gotten a lot of hype out of that relationship. The Who, The Stones and Wayne Berry. But when we went out on tour that Fall, three things happened. We went out to the Midwest and opened for Billy Joel, who was just starting to bust open. The opening night of the tour we played in Kansas somewhere and received three encores. The next day, Rudge's office called and said that Billy Joel's management had called them and were dumping us off the tour. The original contract had us supporting him for six weeks.

“The next leg of the tour was supposed to have taken us to the South and then up the East Coast. We were scheduled to open for Loggins & Messina. Well, it turned out that Loggins and Messina had the same management as Billy Joel. Evidently, someone behind the scenes called them and said, hey, you don't want this guy opening for you. So they pulled the plug on that leg of the tour.

“We're literally in the middle of America with the tour supporting the album unraveling. We started doing pickup dates because we couldn't go back to the West Coast. We did smaller venues and clubs, trying to work our way to the East Coast because we were scheduled to open for Linda Ronstadt in Manhattan. It was late Fall or early Winter of whatever year that was and this absolutely humongous storm front hit the East Coast. The tentative schedule was Manhattan, Boston, Philadelphia and D.C. Linda ended up having to cancel the whole tour because the entire East Coast shut down.

“At that point, we crawled back to L.A. and licked our wounds.

“The label was still solid behind us and there were positive reviews of the album. It was selling. But we lost so much energy. Back then, touring was so important.

“And the band was solid,” Berry emphasized. “Some of the players who really were not yet well known were coming together as my band. A few of the players had played on the album--- James Rolleston had played bass on some of it. He had played previously with Tom Rush and Gordon Lightfoot. He was on that tour. We had a solid guitar player. And we had this B-3 player from Canada. He had hooked up with Janis Joplin and played on her last tour--- the one where she OD'd. He got stuck in L.A. and I ended up meeting him and pulling him right out of Joplin's defunct tour band. He was a fabulous player. We had a kickin' band. But, again, those guys were playing with me predicated on being able to make a living.

“When we got back to L.A., the tour was over. We went out and played some other dates, but I continued writing and eventually went up to San Francisco to work with Elliot Mazer on the next album. I used a few players out of the road band and Elliot brought in some ringers. He brought in Pat Simmons from The Doobie Brothers and Martin Fierro, who was this great horn player, and he brought in Ned Doheny. I knew Ned through Jackson Browne. He was one of the L.A. guys. And there was Merl Saunders and David Palmer. I knew David through Rolleston's work with Steely Dan. We recorded Tails Out in San Francisco but did some overdub work down in L.A.

“When Tails Out was finished, I had some people at RCA in my corner and through some unrelated things, there were some people of power who were a little antagonistic toward me. It wasn't personal, but it became personal.

“The album was done, pressed and released, but had a really limited run. Rolling Stone did a three-quarter page review, which I never did read. I only know about it because Stephen Holden told me about it. It was a beautiful review but it never ran because the album really never came out. There was this intrigue going on and a lot of mine fields got laid and in several situations, blew up. And I had a lot to do with it not coming out.

“The album was probably on the shelf for about an hour”, Berry laughed. “I think maybe ten, fifteen thousand might have made it into distribution.

“I ran into someone who lived here in Nashville who worked in a record store in a mall near where I had grown up. He had gotten involved with my career as a fan, but I didn't know him. I had walked into that store one day and struck up an acquaintance with him based upon the Home At Last project. I received a call from him shortly after the second album was scheduled for release. I was in California and he called from Tennessee to let me know they had product in the store. I had a test pressing of that album, but that was all. And that is how I ended up with a shrink-wrapped retail copy of it. He saved me one.

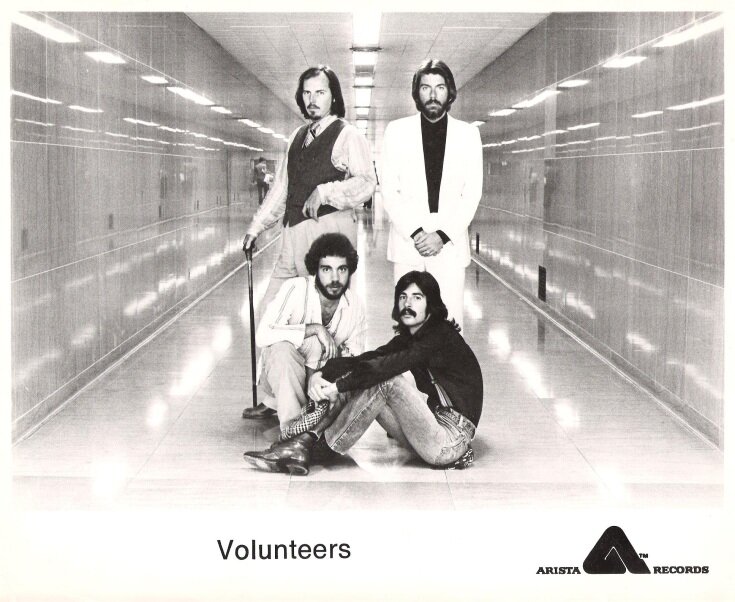

“Everything fell apart at RCA, but before it was finalized the VP at RCA who had heard the demos the secretary had played and had been instrumental to bringing me to the label pulled me aside one night and told me Clive Davis was about to start his own label, Arista Records. Everything was evidently in place behind the scenes for the label to kick off, but it had not yet gone public. What it looked like was that Clive was willing to make me an offer even though I was still at RCA. During that whole transition, George Clinton and I were reconnecting, partially because both of our careers were sputtering. Every time either of us would go three steps forward, we would go two steps back. So we got together and did some demos and put together some pickup bands.

“Clive wouldn't offer us a deal right out, but he wanted to hear us. We met with him at the Beverly Hills Hotel where he had a bungalow. He took us to the ballroom, which was empty. The only people there were Bob Feiden, Clive, myself and Clinton. There was a white piano there, supposedly the same one used in the film Holiday Inn. We played four or five songs with just acoustic guitar and piano and cut a deal right there. Ah, show biz! The stuff dreams are made of.....

“We didn't want to go out as a pre-Hall & Oates or something. We both were band players, so Volunteers morphed out of that. Originally, there were six of us. We rehearsed in Hollywood for several weeks and when the deal was finalized and the front money was there, we decided to go back to Nashville. We needed to get out of L.A. and the plan was to head to Nashville, rehearse and start recording there. Right at the last minute, two of the guys got cold feet. One of them had family. They both pulled out of the band, which was how we ended up a quartet. That really diminished the power of the band. I mean, I'm a competent guitar player, but I'm certainly not a lead guitarist. Both of the guys who left were guitarists, so before they left we had bass, drums, keyboards and three guitars. We were stubborn and doggedly determined, though, and we were already signed. Rather than back up and punt, we decided to go it on our own which was not really a great idea. The Volunteers album has some nice stuff on it, but musically it needed much more attention than it got. The four of us could not really carry what needed to happen.

“We didn't want to go out as a pre-Hall & Oates or something. We both were band players, so Volunteers morphed out of that. Originally, there were six of us. We rehearsed in Hollywood for several weeks and when the deal was finalized and the front money was there, we decided to go back to Nashville. We needed to get out of L.A. and the plan was to head to Nashville, rehearse and start recording there. Right at the last minute, two of the guys got cold feet. One of them had family. They both pulled out of the band, which was how we ended up a quartet. That really diminished the power of the band. I mean, I'm a competent guitar player, but I'm certainly not a lead guitarist. Both of the guys who left were guitarists, so before they left we had bass, drums, keyboards and three guitars. We were stubborn and doggedly determined, though, and we were already signed. Rather than back up and punt, we decided to go it on our own which was not really a great idea. The Volunteers album has some nice stuff on it, but musically it needed much more attention than it got. The four of us could not really carry what needed to happen.

“The album was received coolly and we went out on tour. We held our own, but not all that well, so the dates we played were not very strong. And that is basically how that project wound down.

“To backtrack a bit, between the second RCA album and signing with Arista with Volunteers, I got within--- how would you measure it?--- on a stair with ten steps, I got to about 8 ½ with Atlantic and Ahmet Ertegun. If that had happened, that would have been very interesting because in terms of where I was trying to go, musically, and I guess in terms of my persona if I can put it that way, Atlantic could have been a real home for me, in that time frame. Just before we got in bed together, everybody was speaking the same lingo.

“And part of that whole Rolling Stone review thing? (The review had been written and published in Rolling Stone of the Tails Out album, even though it was decided to not release it) Part of that is that there were people working behind the scenes who were functionally out to get me I didn't know about. As far as I can tell, it filtered down to the people at Atlantic. When it got down to the last meeting before it became a matter of how many zeros to put on the check, I got crucified and the deal fell through. It can happen in any field of work, but what it came down to was that I was sabotaged. And that was a big hit because what was happening with Atlantic and the people and the product line and where they saw the company going, it would have been a wonderful fit.”

Volunteers was kaput, Timber was kaput. It looked like Berry's solo career was kaput as well. Exhausted and frustrated, he returned to Nashville to re-evaluate.

“On a personal level and in terms of ruining one's physical and mental attributes, it was not unheard of for some people to just drop out for awhile. Some re-emerged and some didn't. That, for me, was a difficult period.

“Through the changes that came about after we left Arista, I was pretty fried. I came back to Nashville and tried to regroup and figure out how my life was supposed to work. I think George went back to Chattanooga to do basically the same thing. George met some people who had just opened a studio down on Lookout Mountain. I had this thing I was kicking around, revisiting rockabilly and the like, just trying to figure out where I needed to go next.

“I had a history with Tommy Talton and the guys in Cowboy and I had overlaid with the Capricorn people over the years. At the time, it seemed like a lot of those people were at loose ends--- people who had tried like myself to connect but hadn't. I was reconnecting with Paul Stookey and was just turning the corner back toward having a spiritual encounter.

“Somehow, we got some comp time at the studio on Lookout Mountain and I created this alter ego known as R.W. Knox. I went in and recorded four or five tunes which had a rockabilly vibe, thinking I might want to go in that direction. I was thinking of trying a resurgence thing. I wasn't trying to make a deal. That was just the kind of music I was writing at the time.”

The demos recorded, Berry needed something to keep him going.

“I got involved with MCA Publishing here in Nashville,” he said. “We put a short-term deal together--- something like a year or eighteen months. During that time, I recorded a number of demos and got a few artists doing my tunes.

“Right about then, Leeds Levy, a guy who had been VP at Kapp, gave me a call. He asked what I was doing and I told him I was writing and was just about done with the publishing deal at MCA and he said send me what you got. I sent him some demos and he loved them and wanted to make a publishing deal.

“Things had already started changing for me because of my re-encounter with Jesus, so I told him, here's the deal. I can't guarantee that I will write another secular tune because I am having a spiritual awakening and I'm not sure where it is going to end. If you want to cut a deal, that's fine, but I can't guarantee quotas or anything. He said, just send me what you have and we'll cut a twelve-month deal and see where it goes from there. I made the deal and that was the end of it because I went the direction I thought I was going. I became more and more involved with things of The Kingdom and less and less involved with anything that resembled a career. That in effect uncoupled me from anything in the music business related to a profession.

“As I was coming out of that contract, I had quit playing. I had put my guitars under the bed. This whole encounter with The Holy Ghost began to realign my life.

“Now, what was happening in the Christian music industry was that Contemporary Christian music was surfacing. A lot of that music was just starting to migrate here. A lot of the Christian labels and labels with music which had Christian leanings began to pick up local bands--- rock bands--- people like myself who were getting saved and rededicating their lives.

“I started an acoustic trio and we began being courted by the Christian labels. We had four or five labels after us and recorded a number of demos but could never really come to terms with doing a project which included going out on the road. I had just come out of 20 years of being beat to death by that and thought, this is crazy. Here I am trying to line my life up with following The Lord and you guys are trying to put me right back in the music business. So I did record with that trio, but we never did any masters.

“Out of that, ministry evolved--- lay ministry. I started becoming more and more active with the church and got more and more involved with The Word of God and got more and more involved with in worship as a worship leader. As a result, I became less and less involved as a Christian writer. I wrote for awhile and some musicians covered my songs. I in fact wrote with two or three people and we had several 'Christian hits' which did very well. But I was no longer interested in walking a career path. The more I pursued The Lord, the more it became apparent that The Lord was calling me into worship ministry.

“Here's a rapid-paced version of the last 30 years: getting married, having kids, getting ordained and going into the ministry full-time--- about sixteen years ago.

“I play and sing more now and have for the past 25 years. To say I do it as a living would be a misnomer. My livelihood comes from ministry. I pastor a worship arts ministry department. I rotate out about three bands, each consisting of from eight to a dozen players. We have a choir which consists of from fifteen to 30 singers depending upon the moment. I oversee a dance ministry which has from ten to 25 dancers at any given point. So depending upon what is happening, I could have as many as 60 to 75 people in my department. And I lead worship. And I write as much as ever, but I write in the context of the church.

“For clarity, let me say that it isn't about religion. It is about relationship. Relationship with The Father, The Son and The Holy Ghost. For myself, it is very public. All of that wandering and wayfaring and prodigalness has been redeemed. It doesn't happen every week, but it is not rare for someone who is older or who has some musical sensibilities to come up after a service and say, 'Do you know who you remind me of?' After they say it, they'll mention one of two people: Van Morrison or Leon Russell.”

That gives you an idea of what Wayne Berry is doing, musically and otherwise, today. It has been a journey--- a long one in some ways and a short one in others. I smile when I think of one of my favorite sayings--- “Use your music for good and not evil.” Wayne Berry has been doing just that his whole life. And never more than now. Is he happy with it?

“I'm happy,” he told me. “I've been happy for over 30 years. The joy of The Lord is my strength. My wife and I celebrated our 30th anniversary together at a bush camp on 135,000 acres of wilderness in South Africa last March.”

When I pointed out to him that he was a lucky man, he responded:

“Not luck. Favor. The favor of The Lord. I am a blessed man.”

And so he is.

Wayne Berry, as told to Frank Gutch Jr.